Oblique Politics

Goolugatup Heathcote Gallery

Bridget Chappell, DIS, Pascale Giorgi, Loren Kronemyer, Curtis Taylor.

How can artists picture their hopes for our future, from inside a society that struggles to imagine change? This exhibition features politically-focussed Australian and international artists that respond to this challenge. Through installation, sculpture, video, and painting, they render their politics in oblique ways – through irony, humour, provocation, deception, and negation. In doing so, they undertake the small but vital work of making change conceivable, so as to one day make it possible.

Presented 3 June – 16 July 2023 at Goolugatup Heathcote.

Catalogue ︎

Roomsheet ︎

Artist bios:

Bridget Chappell is an artist and musician based in Aotearoa and ‘Australia’. Their work often involves rave culture, politics, science, and technology. Chappell works through widely varying media – poetry and essays, contemporary and classical cello, hacked sound technology, podcasts and pirate radio, sculpture and installation. Under the name Hextape, they have released several albums of electronic music. They have worked with young musicians behind bars, in remote communities, and in universities. Chappell’s work has been commissioned by Liquid Architecture, Audio Foundation, unProjects, the City of Melbourne, and Murray Art Museum Albury, among others. Artist website.

DIS is a New York based collective including artists Lauren Boyle, Solomon Chase, Marco Roso and David Toro. Formed in 2010 in the shadow of the financial crisis and global recession, their work usually involves political and technological themes. DIS rose to prominence as the artists behind dismag (2010-16), an arts platform posing as an online culture magazine. Dismag’s critique of politics, technology, consumerism, culture had a major impact on contemporary artistic and critical currents and shaped the development of ‘post internet’ art. The collective curated the landmark 2016 Berlin Biennale, and in 2018 established dis.art, an online video art channel. DIS’ own art is highly collaborative and ranges from site-specific installation, net art, photography, sculpture, and video. Artist website.

Pascale Giorgi is an Italo-Australian multidisciplinary artist based in Walyalup/Fremantle. Giorgi’s art involves politics and history, and often takes the form of sculpture and video. In her practice, the forms of classical culture are subverted through humour and irony to make way for mash-ups, hybrids and missed translations. Giorgi has produced experimental festivals, events, writing, and exhibited in solo and group exhibitions, including at PICA, Cool Change, Private Island, Runway, and Perth Festival. Recently she co-created the celebrated exhibition The Rock Pool at Artsource, at which she also produced an utopian communal dinner banquet. Artist website.

Loren Kronemyer is a US-born artist living and working in lutruwita/Tasmania. Kronemyer’s artwork spans installation, performance, experimental media, and often considers ecological and apocalyptic themes. Her collaborative, research-focussed practice has led to the development of projects with niche cultural groups such as survivalists, professional archers, broom manufacturers, and astronomers. Her work has been presented widely, including at Fremantle Biennale, Dark Mofo, West Space, PICA, MONA FOMA, Symbiotica, and Proximity Festival. Kronemyer also works as part of duo Pony Express, which has presented major performance artworks at festivals worldwide. Artist website.

Curtis Taylor is a contemporary artist working in film, installation, sculpture and painting. Taylor is a Martu artist, and prominent among a generation of leaders from the East Pilbara representing their culture on the national and international stage. His work has been exhibited widely, including at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Dark Mofo, and the National Museum of Australia, and he has participated in historically-significant cultural projects such as Yiwarra Kuju: the Canning Stock Route (National Museum), and We don’t need a map (Fremantle Arts Centre). Taylor presented a major solo exhibition at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts in 2019, and in 2021 presented a solo at Goolugatup Heathcote. Artist website.

Exhibition text:

Things are not going well.

The world’s few billionaires own more than the poorest sixty percent. Half of humanity subsists on less than $5.50 per day, while wealth taxes are at historic lows. Ten thousand people die unnecessarily every day from causes related to poverty. Twenty percent of all children cannot attend school. This is a time of accelerating climate catastrophe and mass extinction, of soaring anxiety, of a slide into political toxicity and sadism.

By and large we nihilistically accept this situation, because in the last several decades, our sense of what is politically possible has lowered dramatically. Things are the way they are, nothing will ever change – there is no alternative.

It is the mandate of art to figure such alternatives. To call the new into being, to imagine how things could be different. But for a certain sort of political artist, one who views our dire situation soberly, this imagination is tempered with a pragmatism. These artists must picture the things as they could or should be, while minding the oppressively low expectations that confine the world as it is today.

So what course is open to them? These artists approach obliquely – they use irony, humour, provocation, deception, negation. Sideways, slippery methods allow expression where a frontal approach would draw rejection. They make the glimpse of alternatives possible, a glimmer of something different and better.

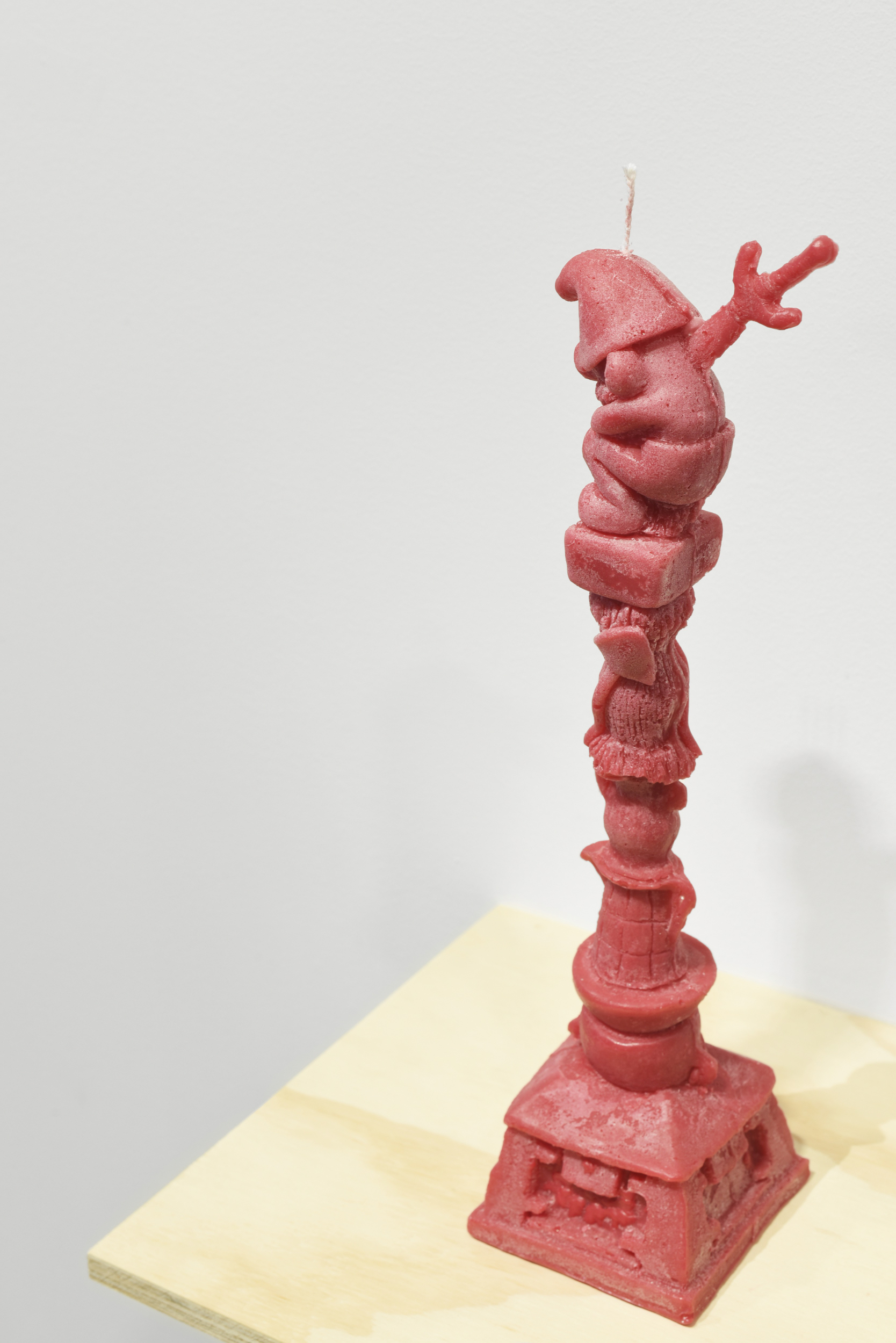

Pascale Giorgi’s art expresses its politics by filtering history through irony and humour. Giorgi’s glazed terracotta sculpture is loosely modelled on the English mediaeval Rochester Castle, once captured by rebels in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, an event symbolically important to socialist history. In Giorgi’s version, the castle contains a living sourdough starter, or ‘mother’, celebrating the tradition and enduring potential of folk politics. At the same time, the work contains an ironic double meaning – sourdough suggests modern home baking, a trend among today’s well-meaning yuppies. The work becomes a sarcastic take on the poverty of ‘political’ action today, its aims, prospects, and its delusions of grandeur.

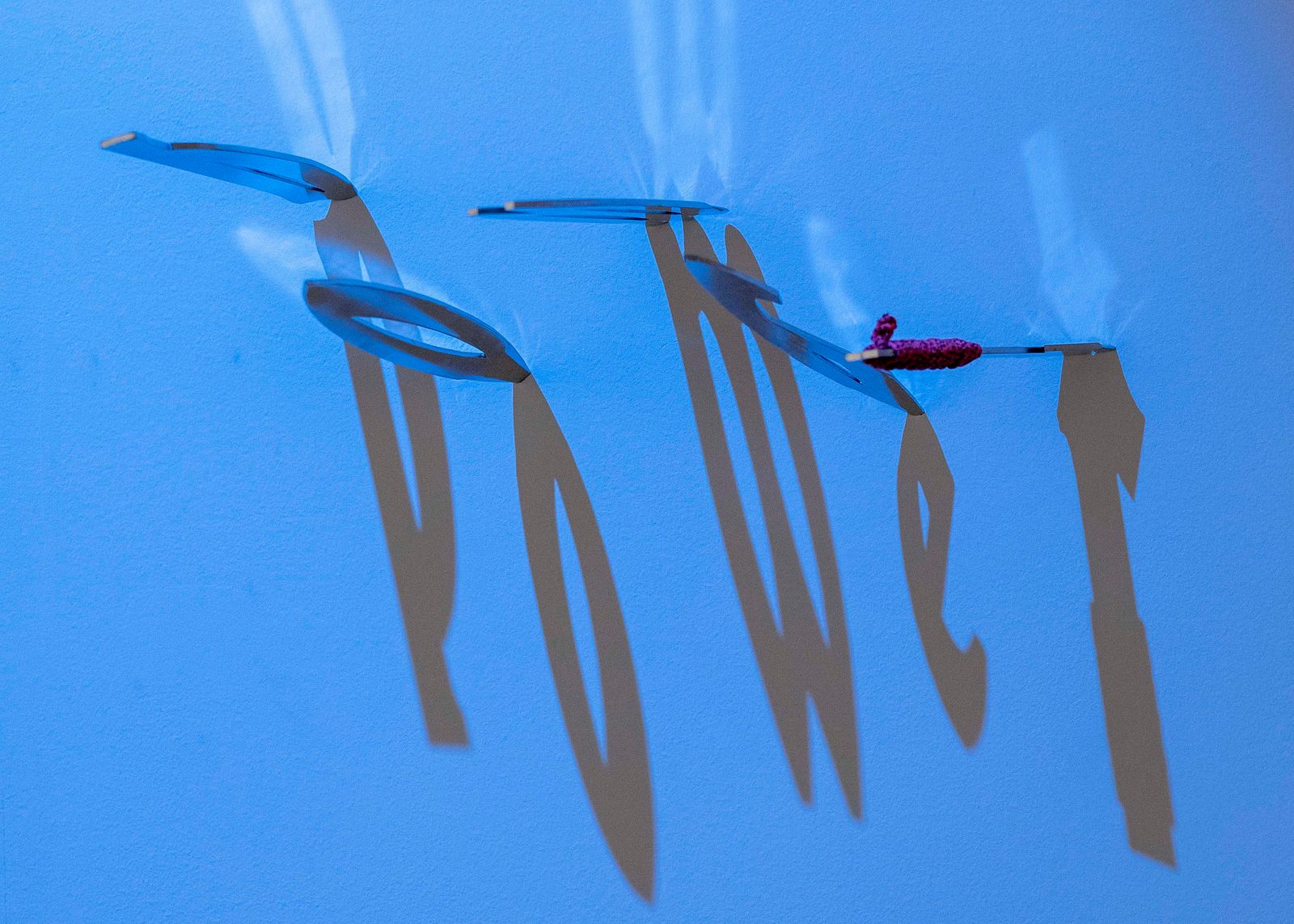

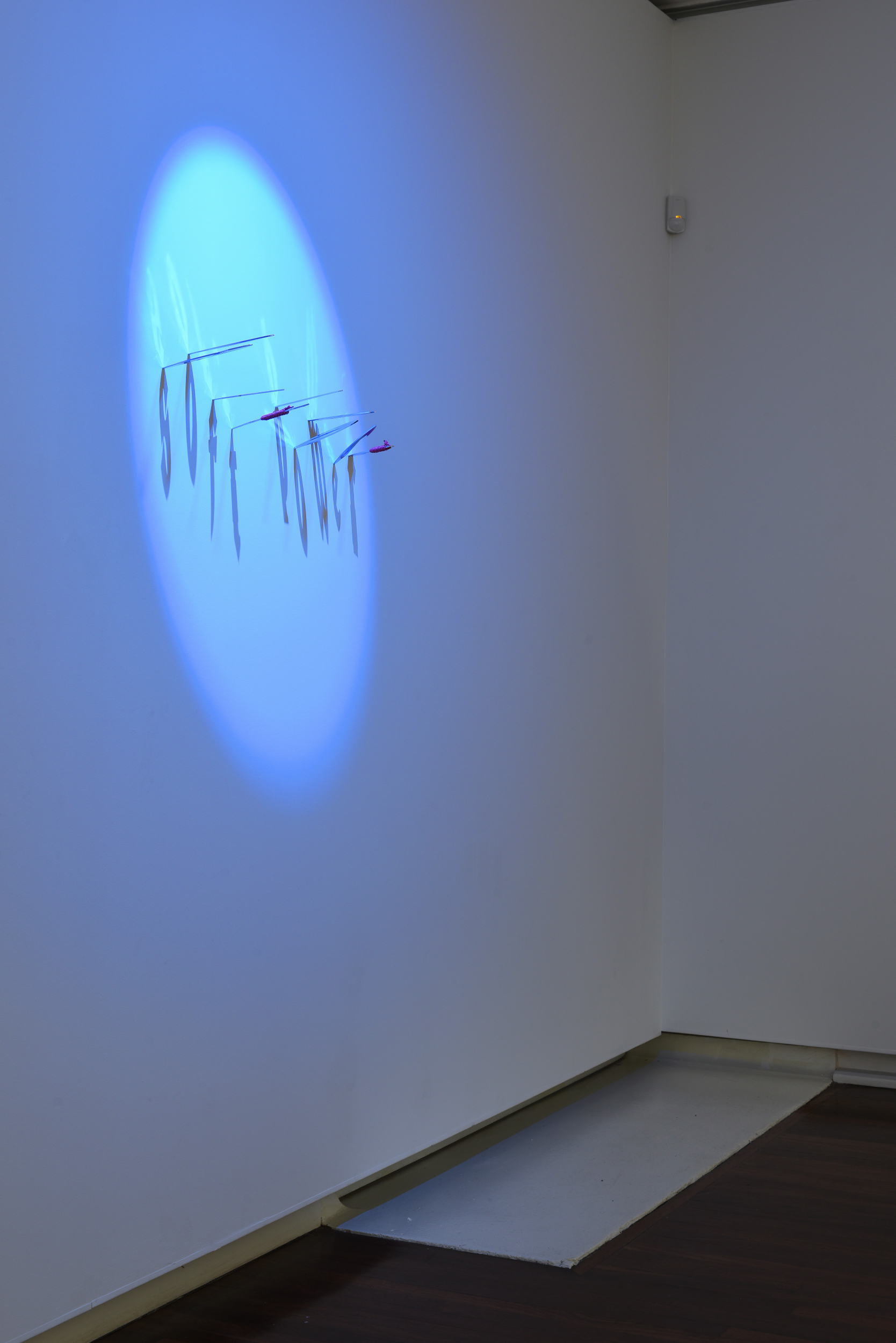

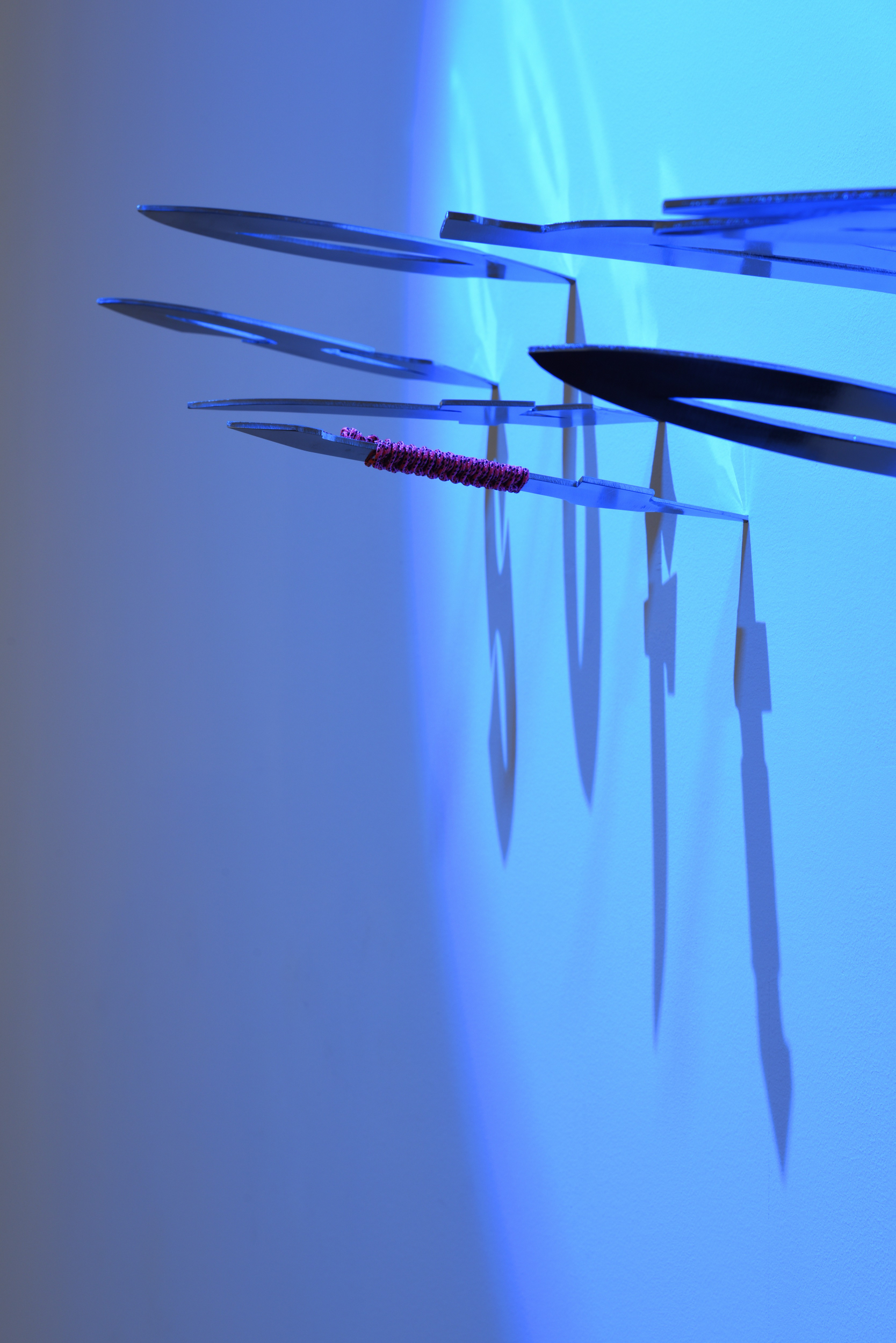

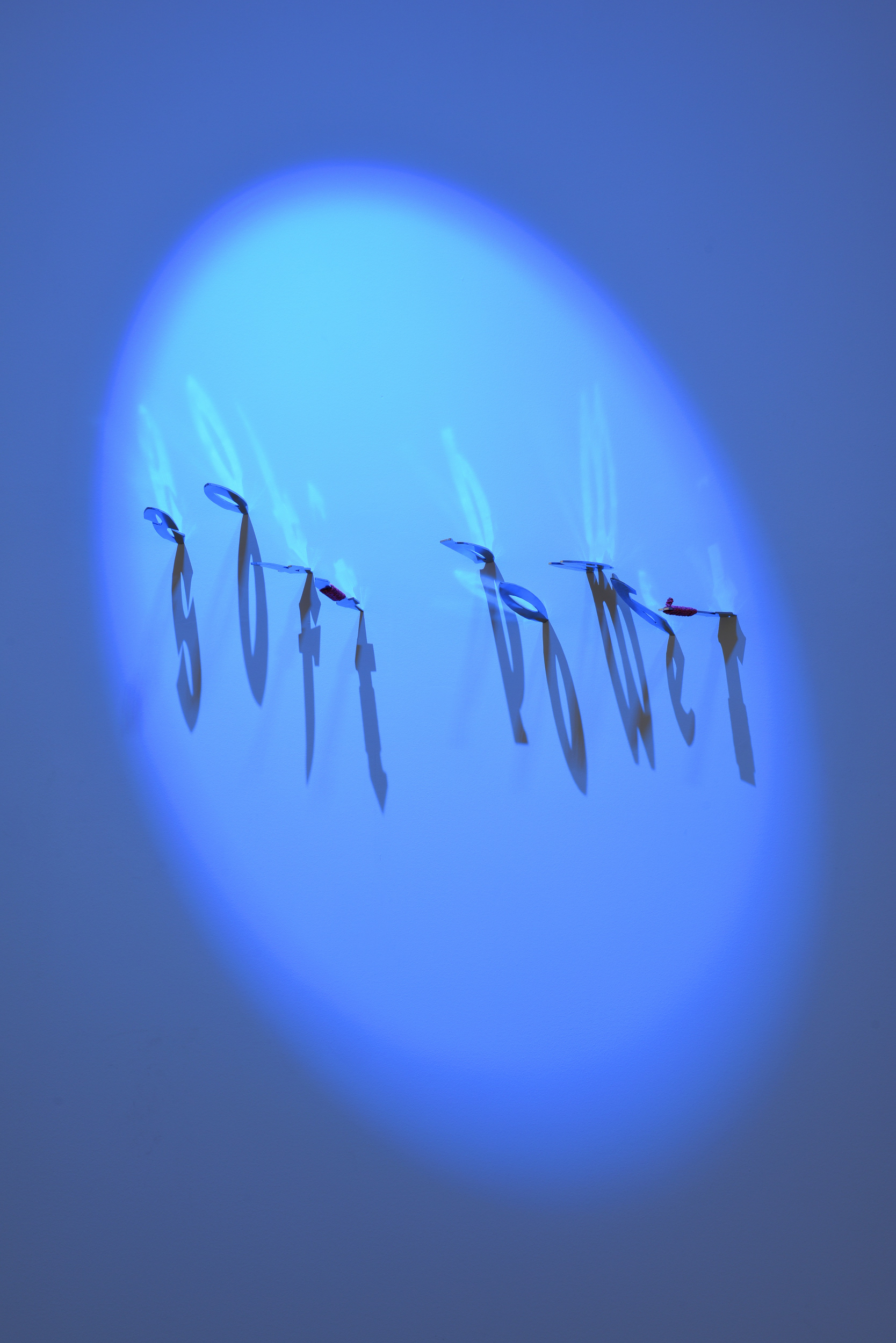

Loren Kronemyer’s art adopts a politics of deception – it appears to say one thing, but really says something quite different. This allows Kronemyer to advance challenging ideas indirectly, making them more approachable. In Autonomous Armory, a set of artist-made throwing knives are embedded into the gallery wall; when lit from above, they cast shadows that read ‘soft power’. On a surface level, its message is clear – the world of culture and force are overlapping and inextricable, soft power = hard power. Deceptively, the work also advances a second, more difficult, meaning. These knives reference an existing consumer culture, but they were labouriously handmade by Kronemyer while living off-grid in rural Tasmania. This is the autonomy of the artwork’s title – the weapons are made consciously outside of the capitalist system of objects. In this light, their meaning flips – they are the artist’s tools, charged with their intent, and their potential violence.

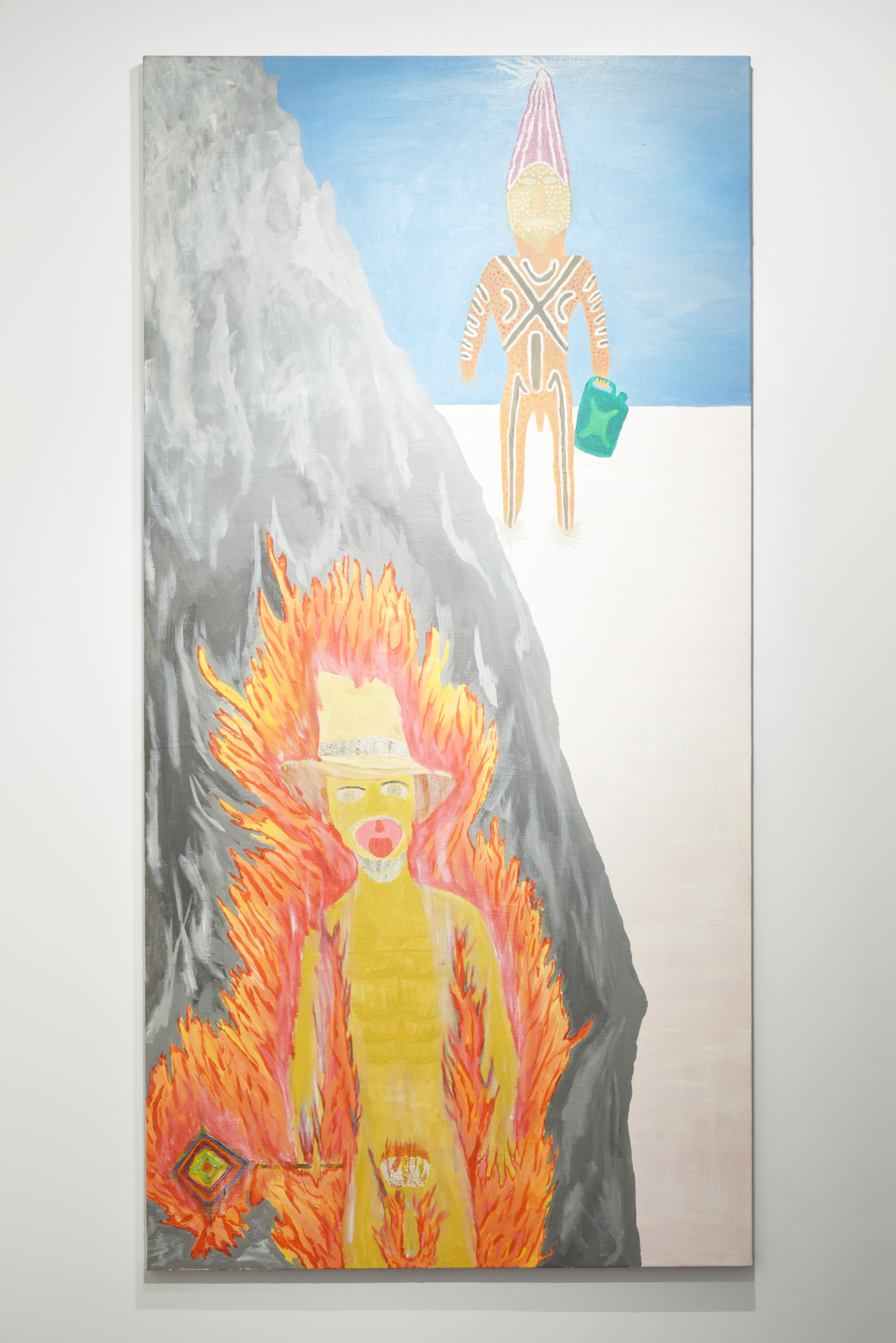

In contrast, in Curtis Taylor’s painting, politics is expressed through provocation. Taylor presents an anti-colonial revenge fantasy, in which an ancestor spirit serves Martu justice against a settler. In the settler’s hand is a stolen sacred item, and in the ancestor’s is a jerrycan of petrol, used to set the white man ablaze. Taylor’s work provokes through its rude frankness in style, its glee in imagining violence. Politically, it is a refusal to be subtle towards the complexity of history, to play nice, to be sensitive. In this way it mocks the moderate viewer and their apparently reasonable attitudes. Taylor’s approach allows him to circumvent normal politics – which considers its subjects with either placid reason or ‘constructive’ optimism. But to face a situation with too much optimism is to express too much confidence in the status quo. Taylor’s political approach is more effective because it is equal to its subject – that is, the situation of colonisation continues to be intolerable, and this work renders that veiled reality plain.

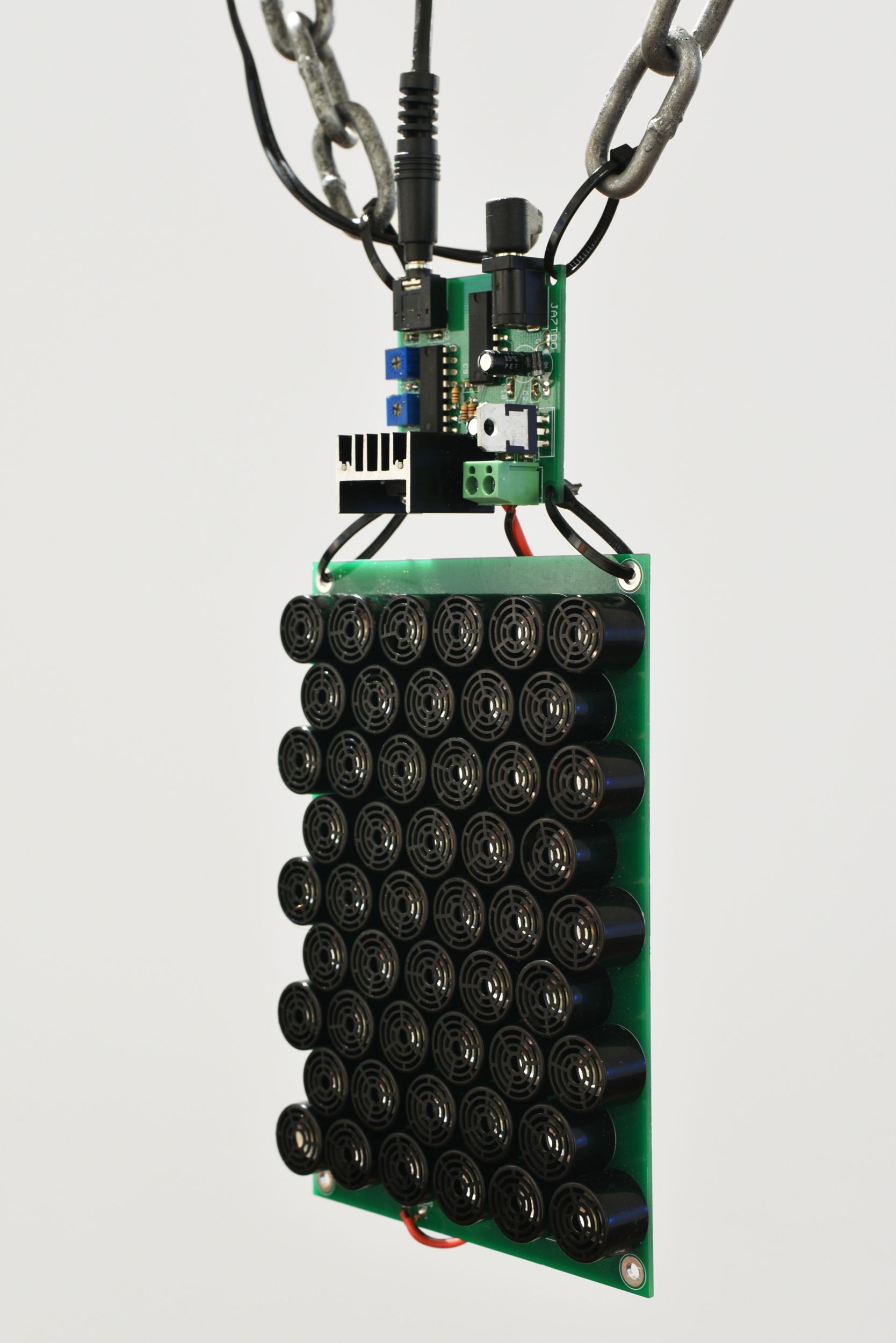

Bridget Chappell’s artwork features a DIY noise-cancellation device, a technology the artist proposes to ‘phase cancel the cops’: to neutralise police communications and sonic weapons. In this installation, this device is arranged opposite such a weapon – an LRAD, or sound cannon, now used by police against public demonstrators. Chappell’s installation creates a zone of audio phase-cancellation against the LRAD, conceptually liberating a space from political control. Unlike more conventional political art that tends to suggest a particular political program, Chappell is not directing how this liberated space be used, rather it is an assertion of the potential for freedom. The artwork is pragmatic on this front – beyond its conceptual artistic purpose, the noise-cancellation device is a working prototype of a practical protest tool. In both its practical and theoretical modes, Chappell’s artwork proposes negation as a productive political method, and a possible germ of our liberation.

In DIS’ video artwork, an artist tries to explain the concept of money to children. The work uses self-critical humour to express its politics, drawing the viewer inside a deceptively sophisticated and radical conversation. Slowly, through simple language, the artist describes to the children the absurdity of money, the injustice of work, the concept of surplus value, and even suggests an abolition of the capitalist order. Because children can accept ideas without preconceived notions, the ideas cut through – the viewer sees through the children’s eyes, and the spell of capitalist ideology starts to break. The work offers a chance of escape from the ‘realism’ of neoliberalism, a worldview that forgets the future is contingent, and sees only the present, rolling terribly on and on. At the same time, DIS’ art maintains a strain of self-critical humour that implicates their would-be comrades. They reflects a problem at the heart of radical politics today: the struggle to pronounce an alternative. DIS understands they must take an oblique path to picturing a better world – but that this path may resolve to be the shortest route.

Curator: G. Louden. Install coordinator: J. Wansbrough. Photographer: D. McCabe

Additional thanks: L. Hansal, L. Craft, T. Meakins, J. Braddock, L. Blue.

Documentation: Dan McCabe - artdoc